Tender Trends: Then and Now chronicles the evolution of the procurement process — from its early days of materials ordering to its rise in shaping policy implementation, industry innovation and social change. Tender Trends: Then and Now is written by bid management veteran and Bidhive CEO Nyree McKenzie who has dedicated more than half her life to the profession.

In this chapter we cover the major changes that occurred in global procurement at the turn of the decade from 2010 to 2017.

Ethical and green supply chains

The global financial crisis between between mid 2007 and early 2009 disrupted the way business was conducted more than any other modern event, and there wats more to come. ‘Reform and renewal’ agendas swept across governments worldwide, with regulatory change spinning the wheels once again in the procurement of enterprise goods and services.

2010: Human rights and environmental activism

In 2010 ethical and green sourcing emerged with sustainable procurement placed at the crux of business strategy. Beyond taking responsibility for specification decisions, procurement departments were firmly taking the lead to support organisations that could demonstrate ethical working practices — from the sourcing of environmentally friendly materials to anti-slavery principles laid down by the United Nations.

The world had already been exposed to the exploits of the food and clothing sectors, and so any risk to brand or reputation — by direct suppliers and those along their supply chain, would be scrutinised. Tenders soon demanded more than just high-level statements of principle and asked for action plans to ensure local labour and environmental management plans would be implemented.

If corporations wouldn’t do it of their own accord, procurement would have to become the instrument to force social change.

Time-to-market was becoming more compressed with tender deadlines being brought forward — what once was a four to six week window between RFT release and submission date shrank to as little as 3 and 4 weeks — in the EU it ranged from 37 days to just 10 days.

Procurement departments favoured all things green and smugly issued electronic templates with limited writing space to ‘save people time’. We also saw a spate of pre-qualification tenders being issued as a way of reducing ‘red tape’ around re-tendering.

2012: Reform of government services

This was also the beginning of government reform. With funding challenges, government saw itself more as an ‘administrator’, with ‘service delivery’ being taken to market and outsourced on a larger scale.

Procurement reform focused on fixed price terms and whole of government contracts were awarded to a reduced panel of suppliers to save time and money spent on contract management.

Road maintenance reform around the world marked the beginning of public road maintenance outsourcing to the private sector. This model, which paved the way for outcomes-driven contracts, promised incentives for private sector contractors that could demonstrate improved road safety features to reduce motor vehicle accidents.

It is a good example of how the industry was forced to shift from tendering for stages of work to adding value through stakeholder consultation with considered, co-designed innovations and solutions involving alliance partners, citizens and government.

In 2012 procurement reform to deliver better and more efficient public services became a priority in almost every state and territory in Australia, and overseas as well. The result was again the resurgence of mega contracts featuring larger geographic footprints and contract sizes, and the subsequent reduction of suppliers in the government’s procurement system.

The flow-on effect to industry changed the way business and government worked with each other -– many more consortiums and joint ventures resulted, with relationship or alliance contracting become a key differentiator for companies as a way to bring more value to the opportunity.

Tenders finally moved beyond being simply compliance documents, to focusing firmly on corporate competitiveness and cultural alignment, governance and corporate citizenship, and the linkages between them. New standards and guidelines were introduced for corporate governance; as well as for bidding, tendering and procurement professionals. It was time to bring the best of the changes into clear frameworks.

2014–2016: Outsourced services and prime contractor dominance

With clearer delineation between policy and service delivery, government continued to commission other public services to non-profit and private sector organisations as a way to drive down costs, and to reward productive and efficient private businesses through incentive or output-based payments. It wasn’t all roses, for corruption had reared its head again.

In 2016 Spain’s biggest corruption case saw 37 business people and politicians, including former members of the ruling Popular Party (PP), go to trial on charges of fixing the government procurement system to steer construction contracts in their friends’ favour. Scandals swept through many sectors, but none more prevalent than in defence outsourcing.

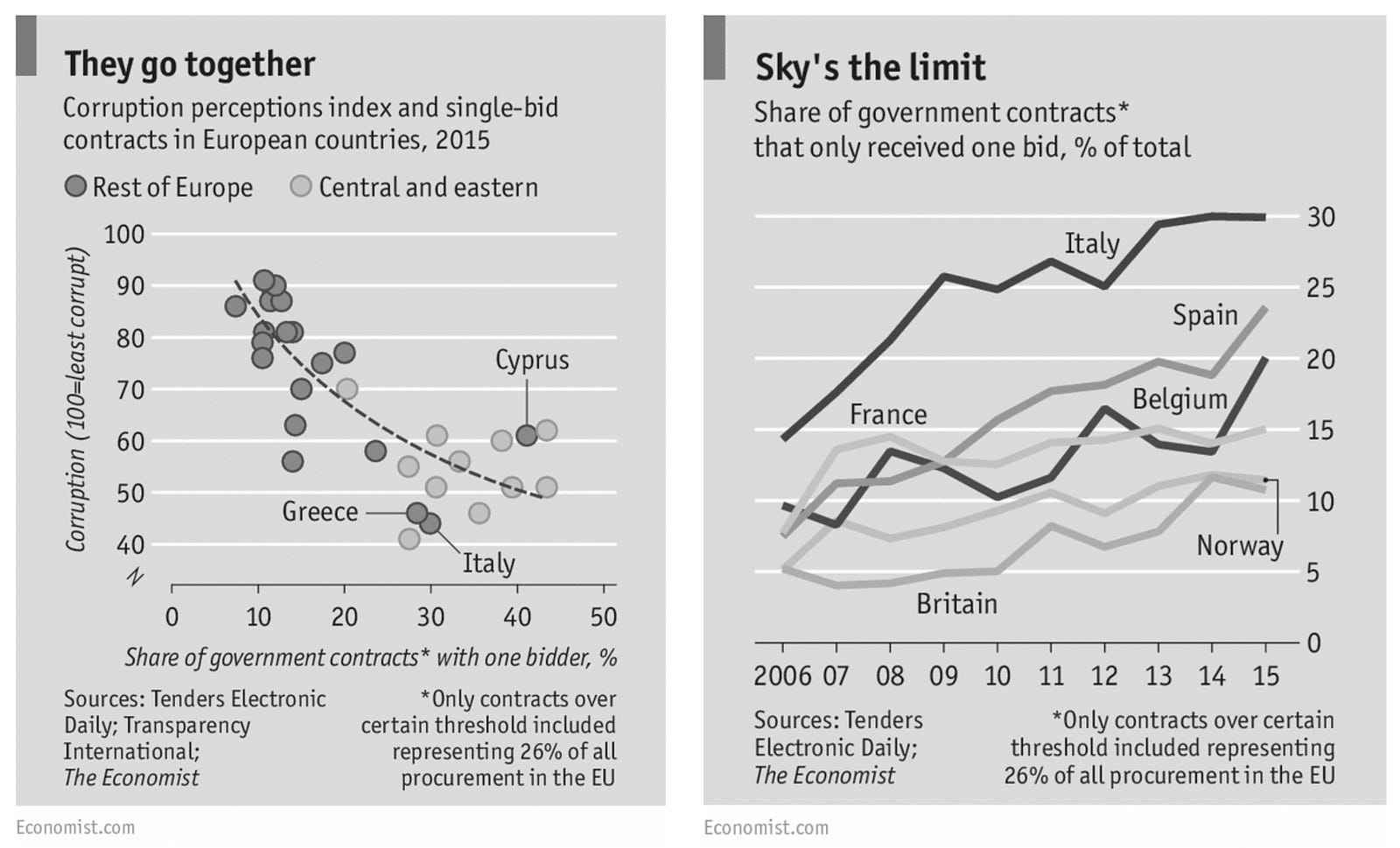

It was a worrying sign, and analysts began to observe an increasing number of single-bid contracts in what should have been an open and transparent tender environment.

While government had been outsourcing services to private contractors for decades, some European governments were contracting far more to fewer companies. This was the beginning of another trend towards the achievement of ‘procurement efficiency’ and the swing against managing multiple contracts.

Worldwide, mega contracts were awarded for the running of facilities such as detention centres, correctional centres, hospitals, aged care in the home, disability services, primary health networks and employment services. In Europe alone, the public procurement market was worth around 1.9 trillion euros, or around 20 percent of its GDP.

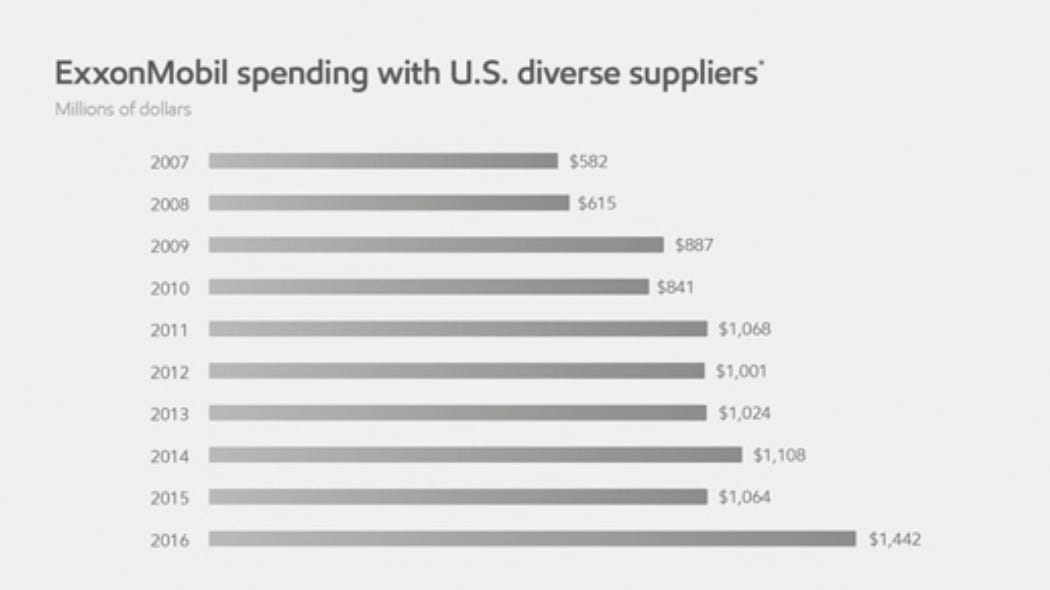

To counter monopoly of supply, governments began to introduce imposed supply chain rules. In Australia, UK and US markets, new regulations around workforce participation, local and small business and minority group inclusion were introduced to correct the market that had been dominated by large companies. Small players were now given a fighting chance to compete.

These new mega contracts promised savings and efficiencies, happily-ever-after socioeconomic inclusion as well as job creation. The public sector also turned to industry to help solve social problems too. Again, the relationship landscape would be changed again, and the bid team competing for a public sector contract would now need to incorporate social outcomes considerations into their collaborative contracting arrangements.

2017: Policy, funding shifts and the new conscious capitalism

Governments all around the world have been acknowledging for some time that they can’t solve the world’s social problems on their own; and to really drive impact, the way they fund and evaluate social programs needed to change. The response to domestic and family violence, long-term unemployment and the rise of chronic disease are just a few examples where non-government organisations and private enterprise began stepping in to help governments take positive action through market-based outsourcing.

The contracts space pivoted once again with the merging — or morphing — of disciplines. The traditional commercial tender format, with its focus on value for money, innovation and outcomes-driven solutions moved into program funding space — for good cause.

Faced with funding challenges, government continued to divest its involvement in direct service delivery to focus on its core business of contract management, administration and policy. And with the widespread commissioning of public services to non-profit, non-government and private sector organisations, procurement introduced a new measure of accountability — monitoring and evaluation.

The result of this new contestable market was the competitive yet collaborative network of community, non-government and commercial agencies clamouring for their share of an integrated inter-agency response to deliver localised services closer to the people.

To differentiate, organisations introduced evidence-based data, research analysis, technology and a range of assessment tools to measure not just outputs, but program outcomes and impact. Health programs would soon have to justify their funding with evidence of reduced hospital admissions; while employment services would have their government incentive payments withheld until their clients had been retained for at least six month in the workforce.

Local needs assessments and innovative service design featured strongly in the best funding and tender applications, and measures to assess the impact of the service model, practice and community outcomes were helping government and industry make better, more appropriate policy and commercial decisions.

New fiscal models emerged, such as social impact investments set up by private equity and banks with the intention of generating social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. With small to medium enterprise participation rising to 26 per cent of all Australian government contracts (and exceeding the 10 per cent target), the gates to small business involvement were finally opened.

Read more

Tender Trends: Then and Now Chapter 1 – Clerical

Tender Trends: Then and Now Chapter 2 – Corruption and Cost Cuts

Tender Trends: Then and Now Chapter 3 – Collapses and Compliance

Tender Trends: Then and Now Chapter 4 – Chains of Command

Tender Trends: Then and Now Chapter 5 – Citizens